The secret [to scientific success] is comprised in three words— Work, Finish, Publish.

— Michael Faraday

One of the thing I really like to do when waiting for a connecting flight at a major airport is to spent time at a book store. Not too long ago, I came to this book about the 80/20 principle.

It stands just about 200 pages, which means a quick read and it had reference to Pareto. Being involved in computer optimization problems, in particular involving two or more opposing constraints, the notion of Pareto front is fresh to my mind. Similarly the notion that 80% of the work can be achieve with only 20% of the feature of a software or 80% of the riches is held by 20% of the population or that is takes 80% of effort to accomplish the most demanding 20% of a project are all well-known applications of the discovery made by Pareto.

The book

The book explains the above principle with examples and also discusses how it apply to business, project managements and personal life. As you can expect, it take about 20% of the book to reach at least 80% (if not more!) of the goals set forth by it 😉

Still, overall an interesting and very fast read.

Can it be applied to science?

Well, a lot of what we do in research is program (collection of projects) and project-based. Therefore, it is always worth the effort to ask yourself why you are undertaking a new project, if it will contribute significantly to your overall research program and if the resources needed to accomplish it are available. It may very-well be that you will need to spent an enormous amount of effort (let say 80%!) on a given project such that you will have to halt almost everything else. It better mare sense and pay off!

Can it be apply to analyze scientific productivity?

While reading the book I was wondering if only a small portion of my research program was really contributing to citations and impact on the field. I decide to quickly look at this by using Google Scholar. GS can track citations and h-index base on all of your papers and it takes last than 5 minutes to set-up (go over to scholar.google.com and chose “my citations” at the top right)

I will not providing my absolute numbers here. Still, fair enough my h-index is such that the value corresponds exactly to 20% of my published papers i.e. 20% of my published papers contribute to my h-index value. For example, for my h-index was 20, this would means that 20 papers have 20 or more citations and, it would also corresponds to the 20% most cited among 100 published manuscripts.

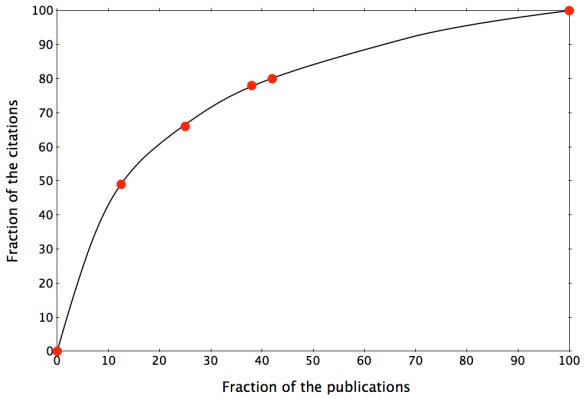

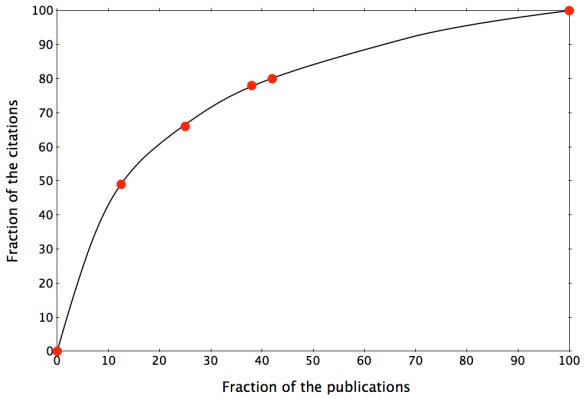

Next I look at the citations of each paper individually. On the figure below, you will find the fraction of total citations as a function of the fraction of manuscripts published.

It is quite interesting to see that a small fraction of all papers account for the majority of the citations. In my case, 13% of the manuscripts contribute to 50% of the citations and 42% contribute to 80% of the citations. So yes the Pareto principle is at play, but…

Limitations

If you were to ask me about each paper included in the 13% that gather 50% of the citations, I would reply:

- Some I knew as we were preparing it that it would be important to the field.

- Some I thought would be important but are not cited so much.

- Some I thought were curiosities that would be of interest to only a few but ended-up as my most cited papers.

I think you get the message…

Conclusion

I can prove anything by statistics except the truth.

— George Canning

Yes, you can make statistics say anything. In the context of a creative process, predicting which of the creative action (here paper) will become a hit is actually rather easier after the fact than the other way around. Therefore, the concept might be interesting to track your resources (grant dollars, materials, projects to start, …) but it cannot be used, as expected I guess, to help you predict your future creative hit wonder!